|

|||

|

Most Yesterland articles are about things that are gone, but this one is about an opportunity to visit the future—as envisioned in 1946. But first, let’s remember Disneyland’s Monsanto House of the Future. It was futuristic when it opened in 1957, but had become embarrassingly dated just ten years later. That doesn’t mean plastic houses had become commonplace—only that styles and expectations had changed. The solution in 1967 was demolition. If only it had been saved! It would now be a fascinating glimpse into how visionaries of the past imagined the future. You can still tour another highly original “house of the future” today—from 11 years earlier than the one at Disneyland. It’s in Dearborn, Michigan. And the visionary responsible for it also deserves credit for the icon of Epcot.

|

|||

|

|

|||

Photo by Werner Weiss, 2018 The Dymaxion House at The Henry Ford |

|||

|

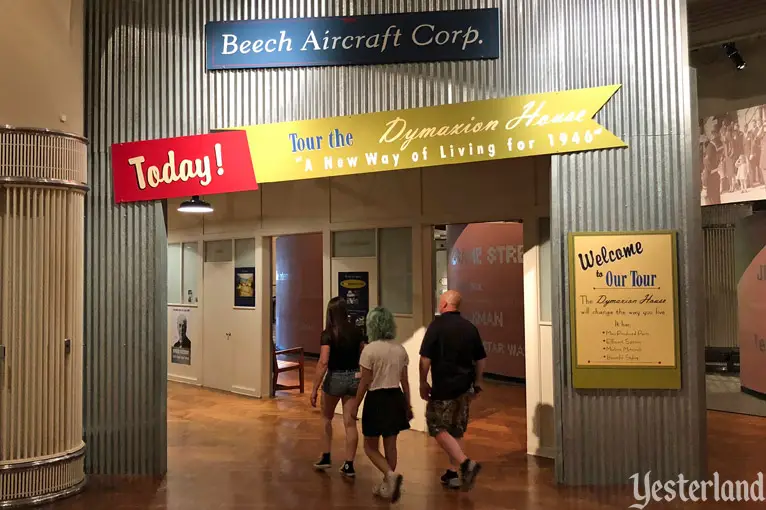

The round Dymaxion House resembles a flying saucer or a giant, foil-wrapped Hershey’s Kiss. The unusual “Dwelling Machine” is tucked in a back corner of the massive Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation in Dearborn, Michigan. It’s one of the many one-of-a-kind exhibits there. This exhibit presents the historical artifact as if were part of a Dymaxion House dealer showroom. Wouldn’t you like to live in a Dymaxion House in a planned community where all your neighbors also have Dymaxion Houses? Traditional houses are things of the past. |

|||

Photo by Werner Weiss, 2018 Tour the Dymaxion House, “A New Way of Living for 1946.” |

|||

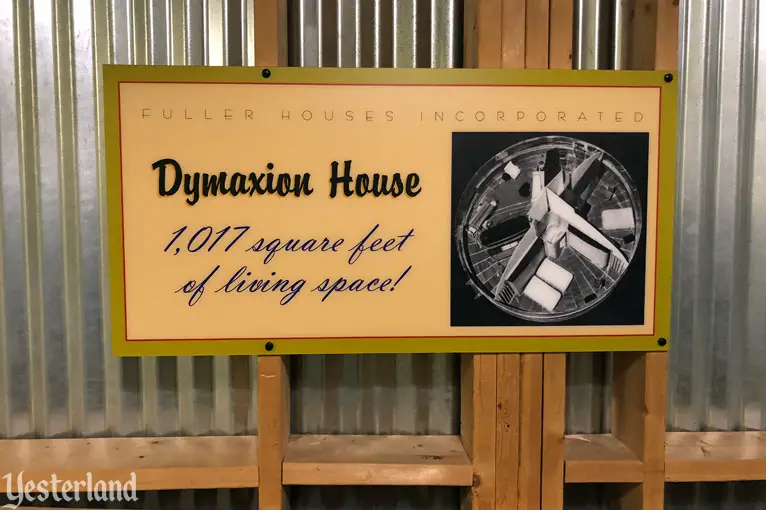

Photo by Werner Weiss, 2018 Square footage and floor plan |

|||

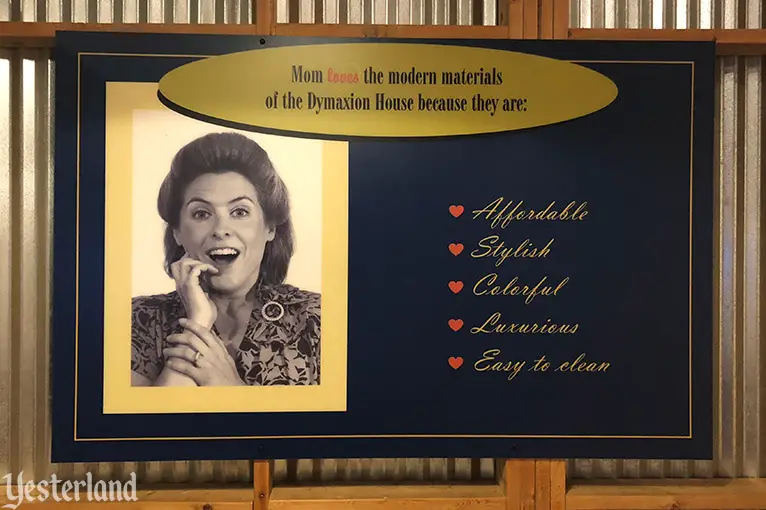

Photo by Werner Weiss, 2018 “Mom loves the modern materials of the Dymaxion House…” |

|||

Photo by Werner Weiss, 2018 “Dad admires the modern materials of the Dymaxion House…” |

|||

|

When the exhibit opened in 2001, the museum gave guided tours. Most tour guides would talk about the house’s history and point out its interesting features. Some more creative guides would play the part of a salesperson in 1946 trying to convince you—the prospective home buyer—to buy your very own Dymaxion House. Now the tours are self-guided, although there are still museum guides to answer questions. |

|||

Photo by Werner Weiss, 2018 Opportunity to admire the exterior and interior |

|||

|

The house is suspended from a central mast which provides all utilities. Although it’s made from lightweight steel, aluminum and plastic, it can withstand earthquakes and tornados. The engineered materials require no painting or re-roofing. The interior floors and walls are plywood. The entire house weighs just 3,000 pounds, compared to 300,000 pounds for a typical conventional home. The price of a Dymaxion House is similar to a Cadillac, so you can pay it off in just five years. |

|||

Photo by Werner Weiss, 2018 Dymaxion House door, resembling an aircraft door |

|||

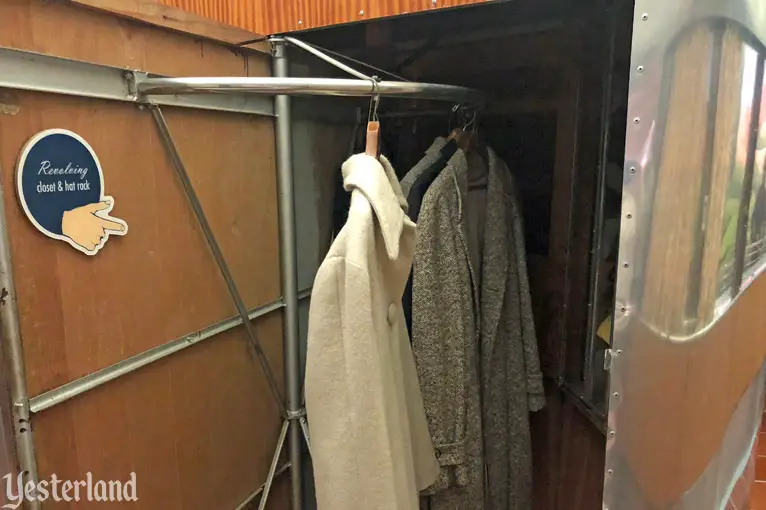

Photo by Werner Weiss, 2018 Rotating closet and hat rack |

|||

|

The tour shows off all sorts of innovative touches: a centralized vacuum cleaner system; a linen closet with mechanized “o-volving shelves” that eliminate the need to bend over; efficient downdraft ventilation that traps dust in baseboard filters; and acrylic windows that wrap around the whole house. The lightweight interior walls separating rooms can be adjusted to increase the size of a room at the expense of another. There are two pie slice bedrooms. One has a bed, a nightstand, and a prefab bathroom—tiny even when compared to an airliner lavatory. The other bedroom is partially unfinished to expose the innovative engineering. A real Dymaxion House would have two bathrooms. The kitchen is modern, with a stove and sink that are just large enough to be useful. There’s room for a full-size washer and dryer. |

|||

Photo by Werner Weiss, 2002 Genuine Heywood-Wakefield nightstand |

|||

Photo by Werner Weiss, 2018 Structural engineering revealed |

|||

Photo by Werner Weiss, 2018 Modern kitchen |

|||

Photo by Werner Weiss, 2018 Panoramic view from the living room |

|||

|

The Dymaxion House—or Dymaxion Dwelling Machine—was the brainchild of visionary inventor, author, and futurist R. Buckminster “Bucky” Fuller (1895-1983). In 1927, Fuller conceived the idea of a factory-produced house that would be affordable, environmentally efficient, and easily shipped. In 1929, the interior decorating department of Marshall Field’s department store in Chicago showcased Fuller’s concept. The store’s promotion manager asked advertising professional Waldo Warren (who is credited with coining the word radio) to come up with a name. After listening to Fuller speak for two days, Warren used syllables from some of Fuller’s favorite words to coin the term “Dymaxion,” with Dy from dynamic, max from maximum, and ion from tension. In 1945, Fuller convinced Beech Aircraft of Wichita, Kansas, that his aluminum house would be the perfect peacetime product for their factories, which had been building World War II aircraft. After all, both products are manufactured from pressed sheet metal. They formed Fuller Houses Inc. The plan was to produce the houses on an assembly line, pack the finished products in large metal tubes, ship them to home sites, plant their central support structure in the ground, and easily assemble complete houses. It would take one day for six workers to erect a house. |

|||

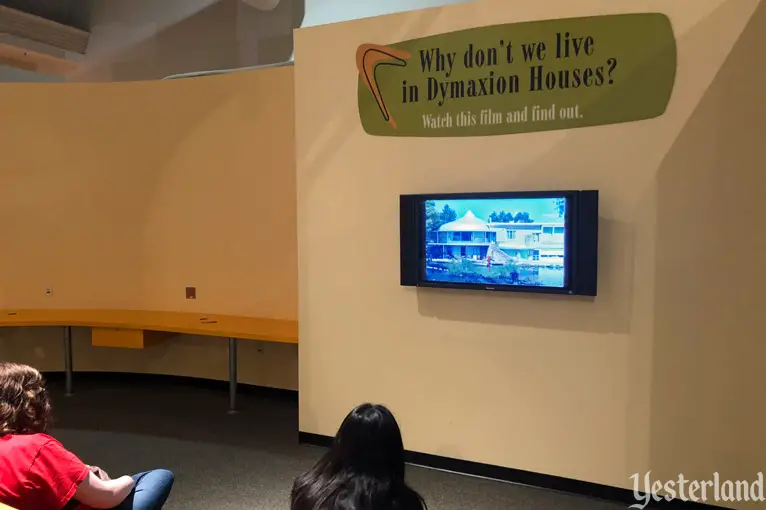

Photo by Werner Weiss, 2012 and 2018 Video after leaving the house |

|||

|

Two prototypes were built in 1945. Disagreements between Fuller and his financial backers doomed the venture. Fuller wanted to refine the design, while the financial types wanted to start manufacturing the homes and selling them to eager post-war buyers. Fuller would not compromise. No additional Dymaxion Houses were ever built. One of the venture’s investors, William Graham, acquired the prototypes from the failed venture in 1948. Graham moved one house to a lot in Wichita and used the other one for parts. He grafted a conventional two-story home onto the futuristic aluminum house. The odd-looking result served as the Graham family home into the 1970s. In 1991, the Graham family donated the abandoned, raccoon-infested Dymaxion House to Henry Ford Museum & Greenfield Village. Representatives from the museum disassembled the house into about 3,000 components. Everything fit into a single truck headed to Dearborn, proof that the house was designed to be easy to transport. In 1998, conservators began the job of analyzing all components and developing a plan to restore the house to its original glory. After a careful two-year reconstruction, the Dymaxion House opened to the public in fall of 2001. |

|||

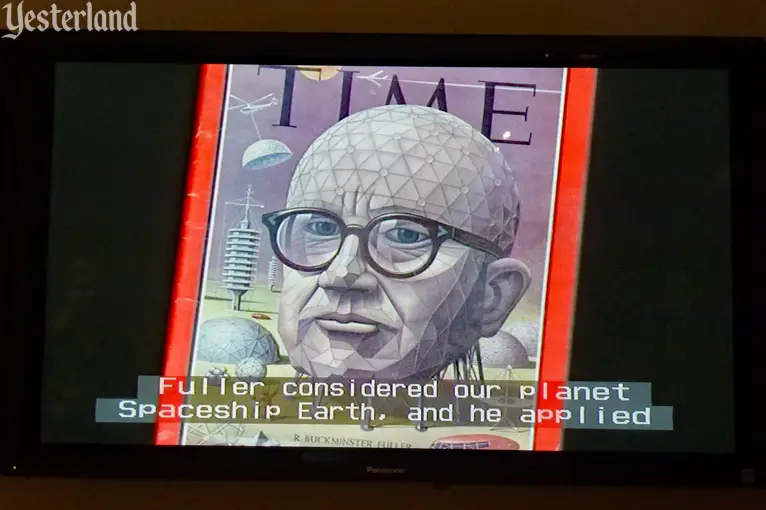

Photo by Werner Weiss, 2012 Time Magazine cover, January 10, 1964, on the video at the end of the tour |

|||

|

Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxion House was a flop, but another of his designs was a huge success. In 1954, Buckminster Fuller received the U.S. patent for the geodesic dome, a partial sphere constructed from a network of triangles. Today hundreds of thousands of people live in geodesic dome homes, usually modest two-story domes built of wood. |

|||

Photo by Werner Weiss, 2006 Spaceship Earth model in Walt Disney: One Man’s Dream at Disney’s Hollywood Studios |

|||

|

Spaceship Earth at Epcot owes two debts to Fuller. Essentially Spaceship Earth is a spectacular geodesic dome on a raised platform, with a smaller upside-down dome below the platform. Together, the two domes form a full sphere. Fuller coined the term Spaceship Earth as the author of the book Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth. |

|||

|

|

Click here to post comments at MiceChat about this article.

© 2008-2018 Werner Weiss — Disclaimers, Copyright, and Trademarks Updated July 6, 2018. |

||