|  |

WESTCOT Center

and the Original Disneyland Resort

Guest Contributor: Sam Gennawey

|

Part 2 of 2

|

|

In Part 1, urban planner Sam Gennawey described the challenges that The Walt Disney Company faced in trying to turn Disneyland into a multi-day destination resort.

Sam is the author of SamLand’s Disney Adventures, a blog about the history and design of Disney theme parks, from which this article is adapted.

If you haven’t yet read Part 1, please click here for Part 1 before continuing.

Now, in Part 2, Sam takes you on a trip through WESTCOT Center and the Disneyland Resort, as it was originally envisioned.

That’s followed by a brief history of what eventually happened to the plans.

Once again, there’s terrific color artwork from the Preliminary Master Plan for The Disneyland Resort.

, Curator of Yesterland, December 18, 2009 , Curator of Yesterland, December 18, 2009

|

|

WESTCOT Center and the Original Disneyland Resort, Part 2

by Sam Gennawey

Let’s take a trip through WESTCOT Center.

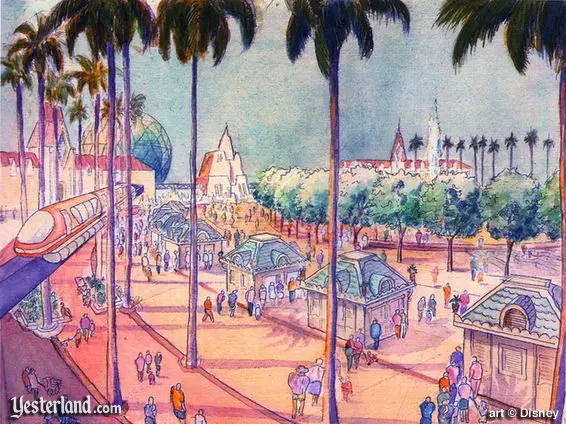

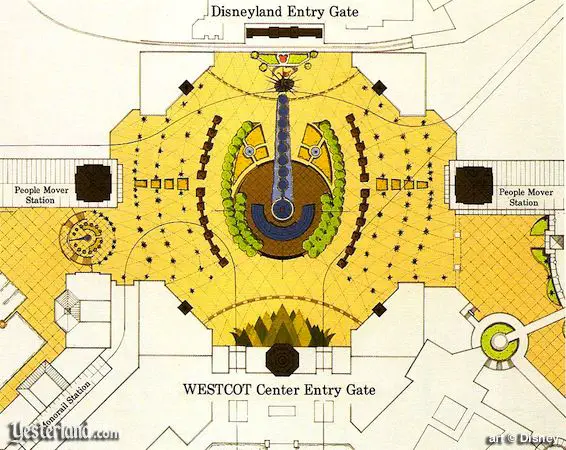

Our trip begins in the Disneyland Plaza. This is the pedestrian and transportation hub for the resort. The Plaza was designed to be a world-class public space featuring fountains and extensive landscaping. You only get once chance to make a good first impression and this was the Disneyland Resort’s center.

|

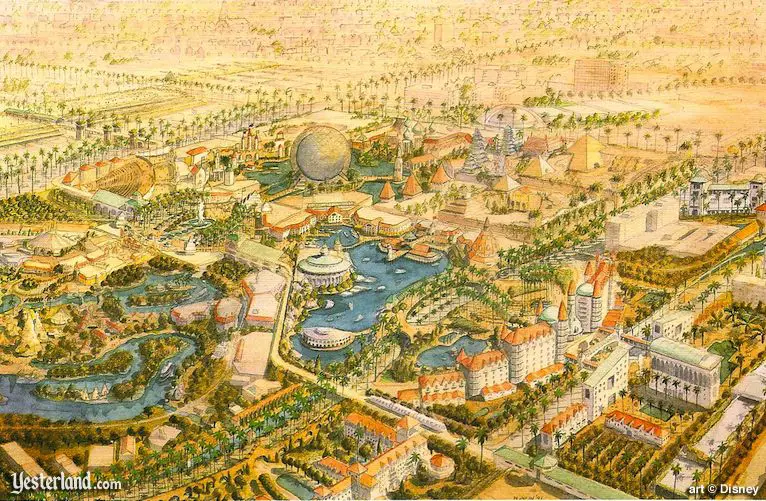

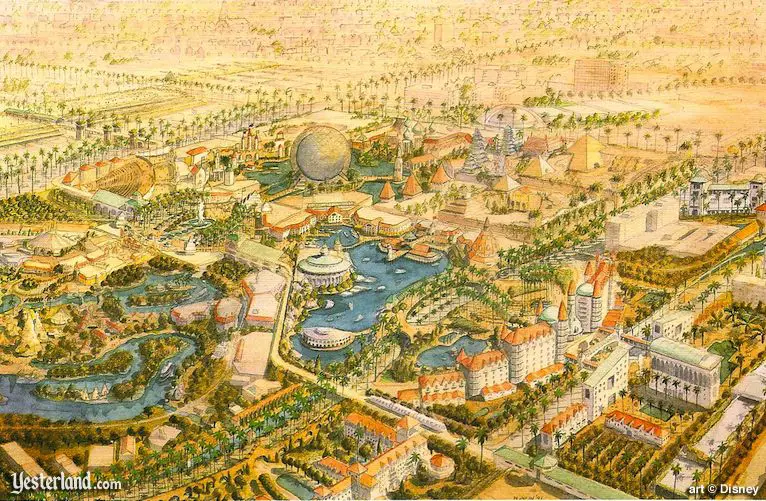

Disneyland Plaza sits between Disneyland and WESTCOT Center.

|

|

EPCOT Center has been compared to a World’s Fair. This is a reasonable observation. A World’s Fair features pavilions that are distinguished by monumental architecture and tied together through landscaped spaces. The pavilions would represent a single concept or project the culture of a particular interest. All of this would be tied together with hyper landscaping, water, sculpture, motion, food, and attractions. WESTCOT Center would be completely different.

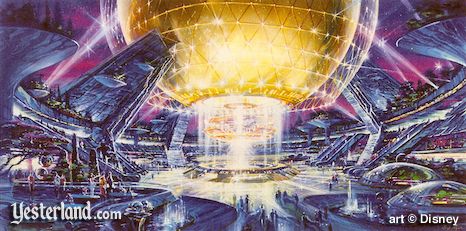

Turn toward the WESTCOT Center entry gate and be prepared to have your jaw drop to the floor. Welcome to Spacestation Earth and the Ventureport. Before you is a 300-foot golden sphere enclosed within delicate latticework of metal. This geosphere is set on a lush green island. By comparison, EPCOT Center’s Spaceship Earth was a mere 180 Feet.

|

Mighty Spacestation Earth is the focal point and icon of WESTCOT Center.

|

|

You cross over a bridge and walk under a cascading waterfall. Beyond the waterfall is a huge lobby. From this point you can ascend into the globe and ride the signature attraction, an updated, next-generation Spaceship Earth or you can proceed to the Ventureport.

The Ventureport is “a futuristic gateway from which guests embark on magical journeys to the Wonders of WESTCOT themed pavilions.” The pavilions include the Wonders of Living, Wonders of Earth, and Wonders of Space. On the perimeter are the four pavilions in the World Showcase known here as The Four Corners of the World: Asia, Europe, The Americas, and Africa.

All together you would have “The Seven Wonders of WESTCOT.”

The focus of Future World would also be different. WESTCOT Center would not be a passive place as guests would be invited to participate. Attractions would be more interactive, and the environments more immersive.

|

The 1991 version of the Disneyland Resort included an amphitheater on Harbor Boulevard.

|

|

All of the Future World pavilions would be indoors. This would allow the Imagineers to use the massive spaces like soundstages with maximum flexibility and control. Tony Baxter said, “We hope that when you come away from those experiences you will have less fear and apprehension about becoming a part of that world.”

For example, the Wonders of Earth pavilion would allow you to walk through exotic environments such as a jungle, the desert, underwater or the Aortic. The Wonders of Living pavilion would be focused on the human mind and body and feature EPCOT Center attractions Body Wars, Cranium Command, The Making of Me, and a unique version of Journey Into Imagination. It would also feature an attraction based Charles and Ray Eames’ “Powers of Ten” film. Wonders of Space would take you on a journey through the Cosmos.

|

|

|

|  |

|

Instead of individual countries, The Four Corners of the World would represent regions. This would allow the Imagineers to blend a variety of influences to make a more powerful emotional impact. It would also simplify the struggle to get international sponsors. So what does a trip around the feel like?

First stop, the New World (the Americas). The entrance would be a companion to Disneyland’s Main Street and create a bond with its neighbor across the Plaza. A Native American spirit lodge would represent Canada and the Mexican fiesta show and restaurant would provide an opportunity to have a margarita and rest. There would be Inca and Aztec spirit shows would add energy to this pavilion. An updated version of the American Adventure would be the centerpiece attraction.

The Old World (Europe) is our next stop. This area would combine high-tech shows and tested attractions. The Circlevision film Timekeeper would find a home here. Imagineers would finally be able to install a show designed for a proposed Russian pavilion in EPCOT Center. A Greek amphitheater will provide additional entertainment. The kids would have fun in the Tivoli Gardens playground. A James Bond-style chase aboard the Trans-European Express railroad featuring famous European buildings zooming past outside the window would be the must-do attraction.

The World of Asia would boast one of the park’s big thrill rides. Ride the Dragon would have been a roller coaster that follows along the Great Wall of China into the Dragon’s Teeth Mountain. The trains would be designed to look like a Chinese Lion-Dragon that you often see in parades. At its crest, the roller coaster would feature red and gold silks that would obscure the view outside the park. Architectural details from Japan, China, and India would be blended together to create a memorable environment.

In the World of Africa you could take a raft ride down the fictional Congobezi River, listen to African drummers, wander through a farming culture exhibit or an Egyptian palace.

The park would have featured the longest ride in Disney history. Connecting the Four Corners of the World and Future World would have been a boat ride called The River of Time. The entire loop would take 45 minutes. You can load at anyone of five points. The trip would take about 9 minutes between each stop. Between stations, you would experience scenes similar to those at EPCOT Center’s Spaceship Earth but related to the land you are flowing under. The scenes would tell the story of the cultures of each pavilion and the evolution of world civilization. When you exit the boat, the station environments would support the scenes you have just witnessed.

|

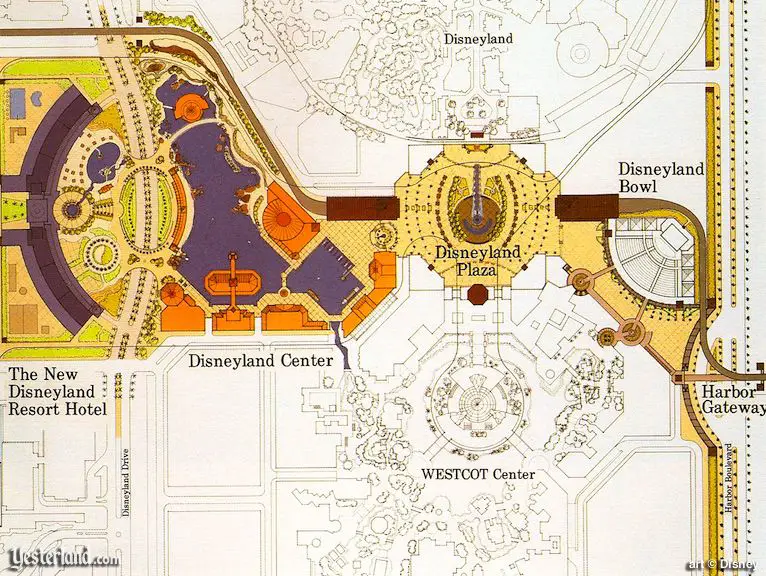

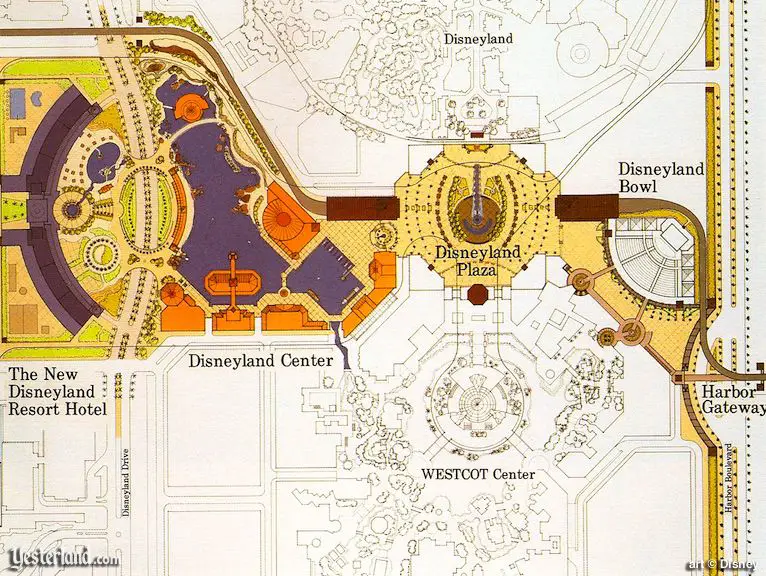

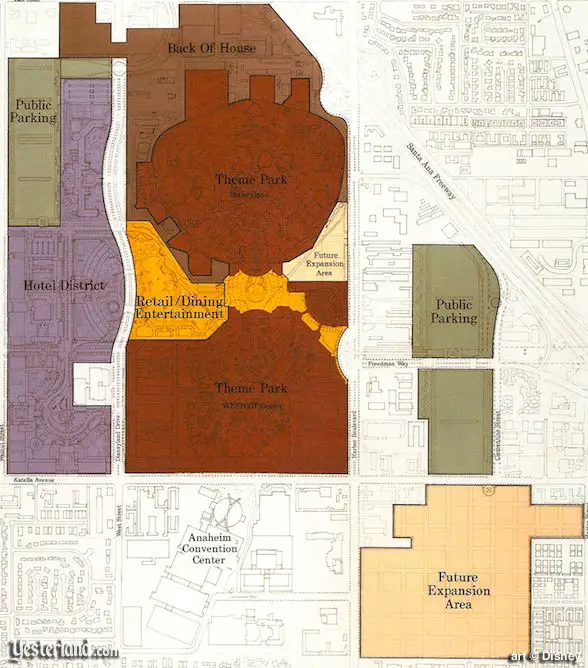

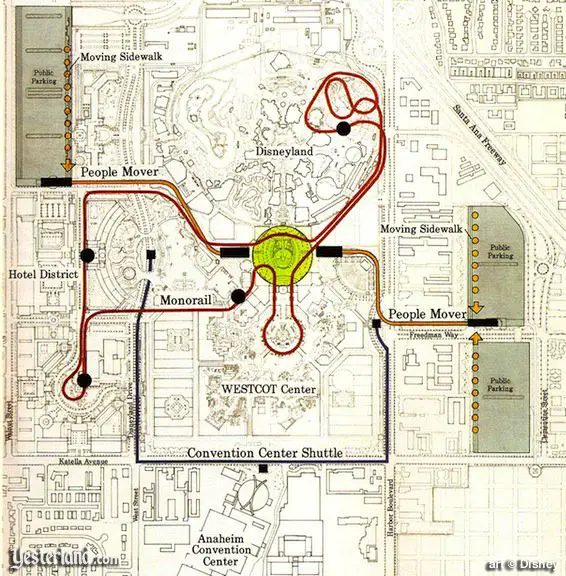

Distinct zones keep similar functions together, with plenty of parking on the perimeter.

|

|

The Resort Hotel District was the real power driving this effort. All in all, the resort would gain more than 4,600 hotel rooms. The road connecting the hotels would be Disneyland Drive. At the north end would be the Magic Kingdom Hotel. Imagine the Santa Barbara Mission with 960 hotel rooms. This would have been one of the moderate hotels.

Continuing south along Disneyland Drive and you come to the New Disneyland Resort. This would be the new top-of-the-line hotel. Like the Grand Floridian at WDW, this 800-room hotel would be based on the Hotel del Coronado. Views into both theme parks would be part of the package.

The Disneyland Hotel would remain and go under an extensive renovation and reconfiguration. A 300-room fourth tower would be added bringing the total room close to 1,400.

At the southern edge would be the largest hotel, the 1,800-room WESTCOT Lake Resort. This resort combines the grace of the Hotel Green in Pasadena and the Beverly Hills Hotel. The rooms would wrap around a six-acre lake with shops and restaurants.

|

|

|

|  |

|

Parkways and a lush pedestrian environment called the Public Esplanade would connect all of the hotels to the rest of the resort. The Public Esplanade would feature the Disneyland Center, the Disneyland Bowl, and the Disneyland Plaza.

The Disneyland Center would be a shopping, dining, and entertainment district around a six-acre lake. The buildings surrounding the lake were meant to recall some of California’s most memorable waterfront spaces including the Catalina Casino, the Pacific Palisades, Venice Boardwalk, and Coronado Island.

The Disneyland Bowl would have been a 5,000-seat amphitheater along Harbor Boulevard and in between the two parks. It would have had a separate gateway and could have been used much like the Universal Amphitheater, which is also connected to a theme park.

|

Disneyland Resort circulation, as planned in 1991

|

|

The Disneyland Plaza would be the transportation hub for the resort. One of the hallmarks of this project was the sophisticated transportation plan. To get to the front gates you could walk, take the monorail or use the elevated people movers from the various parking structures. Landscaping and fountains would enhance the arrival experience.

The parking structures would have been at the perimeter of the resort. The orientation of the structures would have made the walking distance from your car to the moving sidewalk very short. You would step aboard a moving sidewalk that would take you to the PeopleMover system.

|

Detailed view of Disneyland Plaza, with a Monorail station and two PeopleMover stations

|

|

The elevated People Movers would whisk visitors to the Disneyland Plaza where they can board the Monorail with an expanded loop. Like WDW, the Monorail becomes a true transportation system connecting the Disneyland Plaza to a station between the Disneyland Hotel and the New Disneyland Resort, one at the WESTCOT Lake Resort, and Disneyland. The new route would give a preview of the resort and loop around Spacestation Earth just like at EPCOT Center.

Finally, the Disneyland Resort expansion could not happen in isolation. Even back in Walt’s day, the surrounding motels and commercial areas were considered an eyesore. That was Walt’s primary motivation to buy all of that land in Florida in the first place. Eisner needed Anaheim and local businesses to become his partners in cleaning up the area. The City formed the Anaheim Commercial Recreation Area to provide funding of improvements and a regulatory framework. This effort would pay off in district design standards and a consistent look.

It was projected that all of this activity would have attracted 25 million visitors a year by 1998. WESTCOT Center would have drawn more than 10 million on its own.

|

Construction in Anaheim in 2000—but not for WESTCOT Center

|

|

So what happened?

Caltrans, the California agency in charge of the highway system, was anxious to rebuild the Orange County section of Interstate 5. This important freeway connected San Diego, Disneyland, Los Angeles, Burbank, and points north. Money to widen the freeway and to install High-Occupancy Vehicle (HOV) lanes for carpools had been raised by Measure M, a County funding measure. Pressure from Caltrans is one reason why Disney felt it had to act now. If Disney wanted to have the carpools lanes drop cars directly into the parking garages they had to make commitments soon.

The Master Plan was released to the public on May 8, 1991. Anaheim officials certainly knew the benefits of an expanded Disneyland Resort. Estimates suggested that more than 27,000 new jobs would be created, 4,600 new hotel rooms, and $38 to $46 million in new direct tax revenues to the Anaheim General Fund.

But not everybody in Anaheim was excited by this project. Neighborhood groups started to organize. Local business owners like Joe Slutzky who owned Odetics, Inc. were also troubled by what they saw. His company made robotic systems and tape recorders used in the space shuttle. When he saw the plans the only thing he saw was his property already contained within the Disneyland Resort. Nobody had ever contacted him. He was not happy and he was not alone. Disney needed the City to acquire about 100 acres for parking structures and other uses.

Disney had estimated that it would need the City of Anaheim to make a substantial public investment. The first figures were around $880 million. The money would be mostly for land consolidation and infrastructure improvements. Land speculation was rampant and the City was strapped for funds.

By the fall 1991, Disney’s PR machine started to get fired up. First, Disney went straight to the U.S. Congress to try and get $400 million to pay for carpool lane ramps and the parking structures. The claim was the garages would be demonstration projects of space age technology being applied to auto parking. The streetscape plan was unveiled. Campaign contributions were increased and more lobbyists were employed.

In Disney’s December 12, 1991, announcement, they stated that, “our excitement about the decision to proceed with the Disneyland Resort is tempered by the realization that many hurdles remain. Developing a project of this magnitude in southern California is expensive and extremely complex.” Kerry Hunnewell was appointed the Head Imagineer for the project. In a not so subtle hint to Anaheim officials, the press release reminded policymakers that, “a variety of local and regional approvals are required and the fundamental economic feasibility of the project has yet to be proven.” The public’s reaction to the news of the expanded resort continued to be mixed.

|

The entrance to Disney’s California Adventure is meant to look like a postcard.

|

|

By 1992 the WESTCOT Center plans were already being downsized. A proposed Hollywoodland section of the Americas had been removed. The poor start to Euro Disney (later renamed Disneyland Paris) in 1993 would have a profound effect on the entire project. Although The Walt Disney Company claimed that the two projects were unrelated, Roy E. Disney was quoted saying, “Clearly, Euro Disney is making us think twice about a lot of things.” By the end of 1993, Euro Disneyland was on the verge of closing and Kerry Hunnewell stepped down from leading the expansion effort. The project was already a year behind schedule.

The effort to get the Federal government to pay for the parking structures failed. The request was for $223 million but the Federal contribution was limited to $17.5 million. The state of California tossed in $60 million and Orange County paid $36 million. Disney was starting to get cold feet and the community’s opposition to the project was not helping.

By August 1994 the project reflected a new reality. Disney decided to cut the number of new hotel rooms from 4,600 to 1,800. Disney did not want to repeat the overexpansion of Euro Disney in Anaheim. All of the financial forecasts had to be thrown out the window and the already precarious public funding unraveled. Even if Anaheim raise the Transit Oriented Tax (TOT) from 13% to 15% it would not be enough.

Other factors came into consideration. In the early 90s, Las Vegas was on the rise as a family destination. Plus, the land acquisition costs were beyond Anaheim’s ability to raise funds. The projected cost of land purchases was $50 million at a time when the City budget was running a $20 million deficit. Much of the redevelopment agency funds were tied up in the $17 million used to purchase the land for the Honda Center.

|

Paradise Pier shopping at Disney’s California Adventure

|

|

By January of 1995, WESTCOT Center was dead. That summer, Michael Eisner called a three-day summit with his 30 top people. During one of the brainstorming sessions, somebody asked the question of where people go after they have visited Disneyland. The answer was other destinations within California. The light bulb lit up and Eisner is quoted as saying, “California is it. That’s the big idea.”

A new management team was created for the $1.4 billion project featuring Disney’s California Adventure Park, the Grand Californian Spa & Resort, Downtown Disney, the Mickey and Friends parking structure, and various supporting facilities. Leading the project was Paul Pressler, Disneyland President and Barry Braverman as lead Imagineer. Eisner suggested they take a good look at the recently rejected Disney’s America project in Virginia. But that is another story for a different time.

The City of Anaheim scaled back its plans for the Anaheim Resort as well. The City raised the bed tax, expanded the Anaheim Convention Center, and worked with Caltrans on significant improvements to the I-5 freeway including a Disney bound HOV flyover ramp. The City spent $174 million on the implementation of the streetscape plan. Over the past 8 years the landscape has been matured and the area is quite an improvement.

Defending the decision to proceed with Disney’s California Adventure, long time Imagineering Legend Marty Sklar said, “I prefer not to spend six to seven years of my life on something that’s already been done.” He shared Walt’s dislike for sequels. He also felt that WESTCOT Center was conceptually cumbersome.

Sklar thought a park based on California had a great deal of merit. “You come to California and you can’t find it. You know what Hollywood Boulevard is like now and you can’t get into most of the studios. The whole Walt Disney story of coming out from Kansas City as a 21-year old, that’s a real California success story. All of these things add up to something larger in people’s minds than what actually exists here.” His vision for such a park continues to evolve.

An alternate view is attributed to another Imagineering Legend. When asked his opinion of Disney’s California Adventure, John Hench, 65-year Disney veteran and the official portrait artist for Mickey Mouse, reportedly said, “I liked it better as a parking lot.”

|

Disneyland parking lot in 1997

|

Thank you to Sam Gennawey for sharing his knowledge and for the terrific images from the Preliminary Master Plan for The Disneyland Resort!

|

© 2009-2012 Werner Weiss — Disclaimers, Copyright, and Trademarks

Updated February 17, 2012.

Disneyland Resort Preliminary Master Plan artwork © The Walt Disney Company.

Photograph of Disney’s California Adventure construction: 2000 by Allen Huffman.

Photograph of Disney’s California Adventure “postcard” entrance: 2007 by Werner Weiss.

Photograph of Paradise Pier at Disney’s California Adventure: 2006 by Werner Weiss.

Photograph of Disneyland parking lot: 1997 by Werner Weiss.

|

|