|

|

|

||||

|

|||||

|

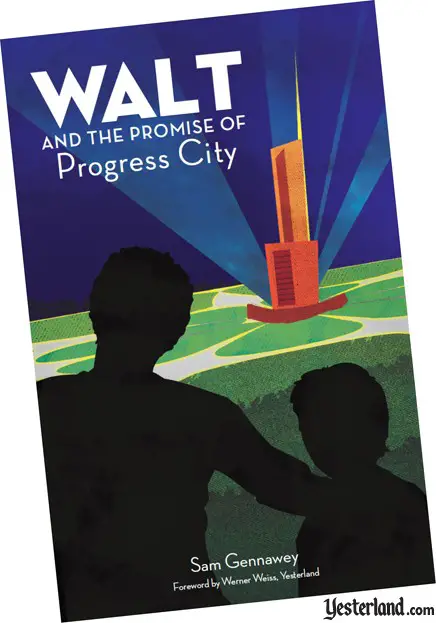

My name is on the cover of Walt and the Promise of Progress City in itty-bitty letters under the much larger name of Sam Gennawey. That’s fitting because I only wrote the foreword. Sam did the real work. It’s his book. Forewords are often written in first person, share personal experiences, describe the foreword writer’s relationship with the book’s author, make the reader more interested in the book that follows, and are fairly short. Ideally, a foreword explains why the book needed to written. I hope I’ve done all that. This Yesterland version of the foreword includes images because—well—Yesterland articles include images. The actual book is not a picture book.

|

|||||

|

FOREWORD It was November 1965. As a pre-teen fan of Disneyland, I was excited by the news that Walt Disney Productions had secretly acquired 27,443 acres 12 miles south of a town I had never heard of—Orlando, Florida. It was an enormous amount of land. I knew that Disneyland had around 60 acres within its railroad loop and probably twice that much acreage for parking and other uses. It seemed that Mr. Disney had enough land in Florida for hundreds of Disneylands—or for an entire city. According to the initial news, there would be a City of Tomorrow, a City of Yesterday, and a number of major industrial plants. There were no details about what Walt Disney had in mind for these cities. The news quoted Walt Disney explaining that it would be three years until opening—a year and a half of planning followed by a year and half of construction. I could hardly wait until 1968. But how would a California teenager be able to visit Florida? |

|||||

Walt Disney, Florida Governor Hayden Burns, and Roy DIsney on November 15, 1965 |

|||||

|

In that pre-Internet era, it was hard to follow newspapers in other cities. I was lucky to have a brother in college on the East Coast who knew that his little brother was a Disneyland fan. When the New York Times published a longer article in February 1967 about Disney’s plans for Florida, he mailed it to me. The article quoted Walt Disney, who had died two months earlier, describing his plans for something that he called EPCOT—the Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow. Walt Disney’s vision was of a real city that would “never cease to be a blueprint of the future, where people actually live a life they can’t find anywhere else today.” So this was the City of Tomorrow! The article said nothing about the City of Yesterday. I was much more excited about the city of EPCOT than any East Coast follow-up to Disneyland. Living in California’s Orange County at the time, I was watching the birth of the city of Irvine. My father had even taken me to the offices of William Pereira to see architect’s master plan for transforming the Irvine Ranch from orange groves and cattle grazing lands into a planned city. Although the Irvine Master Plan seemed to be an improvement over the haphazard growth elsewhere in Orange County, it still seemed so conventional, relying on automobiles and housing tracts, with no public transportation, no revolutionary ideas, and no cutting edge technology. |

|||||

New York Times, February 19, 1967 (text blurred due to copyright) |

|||||

|

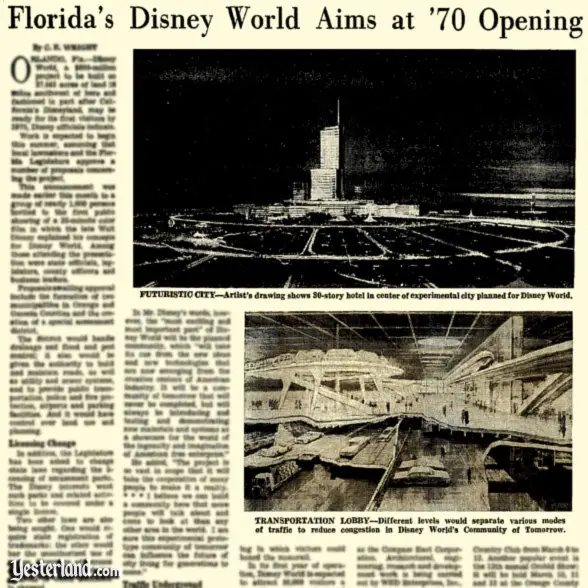

But EPCOT would be another story! The New York Times article described a city unlike any other. No vehicles would he allowed at ground level. Instead, there would be two underground road levels, one for passenger cars and one for trucks. Elevated PeopleMovers—just like the PeopleMovers that would be coming to Disneyland later in 1967—would provide public transportation. An illustration showed a 30-story mega-structure with residential neighborhoods radiating from it in all directions. A cutaway illustration showed an indoor transportation lobby with PeopleMovers, a monorail, and the road levels below them. It was October 1, 1971, before Walt Disney World actually opened. The city of EPCOT was nowhere to be found. It was explained that EPCOT would be part of “Phase Two,” and that what had opened was only the first part of “Phase One.” Visitors had no reason to complain. They were treated to a $400-million extravaganza. The biggest attraction was, and still is, the Magic Kingdom theme park, similar to the original Disneyland, but with many elements larger and more elaborate. The Florida theme park was on the shore of a beautiful blue, man-made lagoon connected to a natural lake. A championship golf course, two resort hotels, a campground, and recreational facilities also clung to the bodies of water. A twin-loop monorail system provided transportation between the distant parking lot, the theme park, and the hotels. |

|||||

Transportation Pavilion concept from the 1977 Annual Report of Walt Disney Productions |

|||||

|

By the time Walt Disney World opened, I was a student at the University of California at Irvine, where I took every class in urban studies and urban planning available to undergraduates. As someone fascinated by cities and by Disney parks, I was still waiting for the city of EPCOT to get the green light—but each year, that seemed less likely. Walt Disney’s successors continued to quote him about EPCOT, but conveniently omitted any references to people living there. During the 1970s, the Annual Reports to the shareholders of Walt Disney Productions included beautiful Imagineering art showcasing concepts for EPCOT, but it evolved into a theme park, not a real city. Epcot Center opened October 1, 1982. My first visit to Walt Disney World was just a few months later. I thoroughly enjoyed Epcot Center—but I couldn’t help but wonder what EPCOT would have been like if Walt Disney had not died the year after he bought the 27,443 acres. Would EPCOT have delighted enough residents and visitors to make it successful—as a business venture and as a living laboratory for innovative urban solutions? Would EPCOT have been able to renew itself continually over time, rather than becoming a stagnant relic from the era when it opened? |

|||||

SamLand’s Disney Adventures blog by Sam Gennawey (as it used to look) |

|||||

|

In 2009, I began reading a Disney fan blog called SamLand, written by a professional urban planner named Sam Gennawey. In this blog, I found someone who shared my interest in cities and Disney. I was hooked. Sam applied his insight and experience in urban planning to explain why guests had such positive experiences at Disney parks. We traded email. It turned out we would both be at the Epcot International Food and Wine Festival that year, so met each other there. |

|||||

Author, blogger, and urban planner Sam Gennawey |

|||||

|

I learned that Sam had always been interested in cites. As child, he would destroy his mother’s flowerbeds developing and rebuilding little cities in them. Instead of taking a direct path toward urban planning, Sam’s career included selling stereos, opening his own record store, running a record company, moving to Chicago to run another record company, joining Mercury/Polygram, serving as the marketing director at a radio station, and inventing a lucrative way to promote records. After all that, Sam went back to college to prepare for a career change to urban planner. Why planning? Sam explained to me that he couldn’t figure out how to make money as a historian, so he combined that passion with his love for the game SimCity. “Voilà! Planner,” as he put it. I was thrilled when Sam told me he was writing book about EPCOT. I was honored when Sam invited me to write the foreword. And I was fascinated when I read Sam’s manuscript. Sam presents EPCOT not as a brief vision in the final years of Walt Disney’s life, but as a decades-long journey that leads up to EPCOT. Sam provides a detailed look at what Walt Disney’s EPCOT would have been like. And, best of all, Sam addresses the question of whether EPCOT would have worked. I’ve been to Epcot many times, but thanks to this book, I’ve now also been to EPCOT.

Werner Weiss, Yesterland.com |

|||||

|

Where to Buy the Book Walt and the Promise of Progress City is available from Amazon in paperback and as a Kindle edition. Also consider these other books by Sam Gennawey. Please use the links below. |

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

In addition to blogging at SamLand’s Disney Adventures, Sam also writes for MiceChat, usually on Thursdays. |

|||||

Sam Gennawey’s SAMLAND on MiceChat.com |

|||||

|

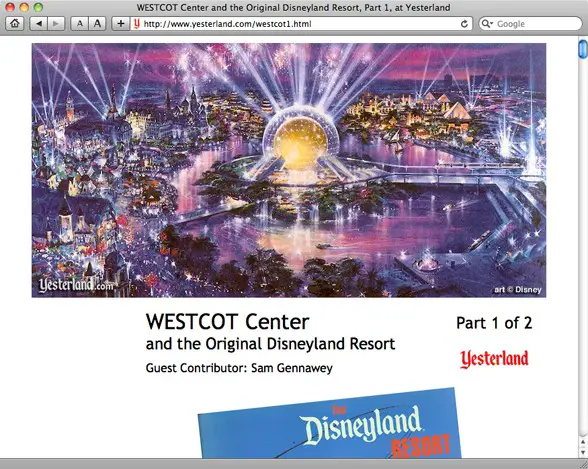

In December 2009, Sam wrote a two-part article for Yesterland about the ambitious plan to expand the Disneyland Park and Hotel into the Disneyland Resort, with WESTCOT Center as the second gate. |

|||||

WESTCOT Center article for Yesterland by Sam Gennawey |

|||||

|

If you missed these articles or you’d like to take another look, here they are: |

|||||

|

|

|||||

© 2011-2014 Werner Weiss — Disclaimers, Copyright, and Trademarks Updated December 19, 2014.

Image of front cover of Walt and the Promise of Progress City: Courtesy of Ayefour Publishing and Sam Gennawey. |

|||||